Sixteen-year-old Avery Roe wants only to take her rightful place as the witch of Prince Island, making the charms that keep the island’s whalers safe at sea, but her mother has forced her into a magic-free world of proper manners and respectability. When Avery dreams she’s to be murdered, she knows time is running out to unlock her magic and save herself.

Avery finds an unexpected ally in a tattooed harpoon boy named Tane—a sailor with magic of his own, who moves Avery in ways she never expected. Becoming a witch might stop her murder and save her island from ruin, but Avery discovers her magic requires a sacrifice she never prepared for.

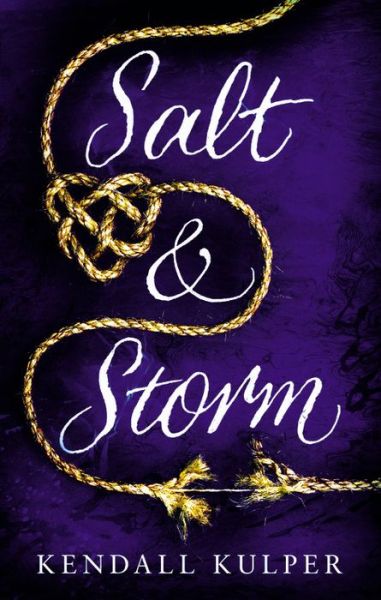

Salt & Storm, Kendall Kulper’s magical historical romance, publishes September 23rd from Little, Brown Books for Your Readers. Check out an excerpt below!

Part One

A Lesson in Killing Whales

One

Despite my mother’s best efforts, I never forgot the day my grandmother taught me how to tie the winds. That was ten years ago, when Prince Island was more than just a rock out in the Atlantic Ocean, when its docks choked with ships, when the factory furnaces spat out a constant stream of thick black smoke and the island’s bars spat out a constant stream of laughing men, their faces round and shiny.

That was back, too, when the people on my island treasured my grandmother and her role in their fortunes. Every man, woman, and child on Prince Island knew the way to her cottage, had to know the way because their lives depended on it.

Even back in the good times, the pastor with the dried?apple face would spend his sermons lecturing the congregation against my grandmother’s promises. A deal with her was a deal with the devil, he’d tell them, raising his fist and cracking it down on the podium. And the people on my island would nod with pinched lips, but they’d visit her all the same.

A man—although they were usually so young they could still be called boys—might ask for a fidelity charm. He’d be anxious, excited, more nervous about leaving his girl than about the years?long voyage he would soon endure. My grandmother would tell him: “Bring me a dozen strands of your sweetheart’s hair and cut off a lock of your own.” Once he returned with the items, her long fingers would weave and bind the hairs with sea grass, building a loose bracelet. “Put it on her wrist,” she would say, “and your girl will remain true.”

Often the boy would hold this flimsy thing in his hand, feeling its impossible lightness, and frown. “You’re mad. This’ll break in a moment and then what will my Sue get up to?”

“Never one of my charms,” she’d say. “Never known one of them to break.”

So he would stick it into his pocket, still frowning, and leave. Later he’d slide it over his darling’s hand.

“Something to remember me by,” he’d say, but the women of Prince Island had seen enough hair and sea grass to know the truth. Still, the bracelet never broke or faded or fell apart and the girl stayed faithful. My grandmother, of course, had no control over the boy.

Older men, the captains and ship owners, kept my grandmother in luxuries like pure white sugar wrapped in crisp paper, fruits so brightly colored they hurt my eyes, bolts of cloth as smooth and soft as skin.

“Caleb gifts,” they called them, because once, many years ago when my grandmother was a young woman, a captain named Caleb Sweeny slighted her, refused to bring her any gift at all, even though he stayed on the island for months as our men restored his ship. Only days after the ship launched, word came back the whole thing had been smashed to bits, run into rocks and beaten into nothing but timbers and torn cloth.

The men of the island grumbled that their months of hard work had gone to waste and worried that their reputations as shipbuilders would suffer. But even today everyone on the East Coast knows there’s nothing stronger than a nail hammered on Prince Island, and so, in the end, the builders kept their fine reputations while my grandmother gained a new one: stormraiser, not to be crossed.

It wasn’t only men who made the walk to my grandmother’s cottage. Women visited, too, women who wanted to protect their men at sea or, every now and then, to curse them. Sometimes it would get tricky: A woman would arrive spitting mad, promising my grandmother anything if only the Kingfisher would fail on the sea and one of those colossal whales would take a mighty bite out of a certain Clarence Aldrich and drag his filthy body to the depths. And this would put my grandmother in a spot, because she had just sold Clarence Aldrich a talisman made from a bit of wren feather, a powerful magic against drowning. Now maybe my grandmother would try to calm the woman and convince her to spend her money on a love charm to find a man not quite so worthy of a bite from a whale. But more often she’d take the money and make the spell and tell herself that Clarence Aldrich would still be saved from drowning, even if the whale might get him first.

These were the simple tricks and common charms and minor spells, paid in trade or food, that kept my grandmother’s life running smoothly. They cost almost nothing to make and barely any time to pull together. Trifles, she called them, the little charms that were, to her, as easy as breathing.

Tying the winds was a different thing altogether. Only the richest ship owners could afford it, and they’d send their captains to the cottage on the rocks with money and instructions. The money my grandmother took willingly, the instructions less so. The winds are tricky, shifty, and it was hard enough, she’d tell them, binding and tethering them without some fool going on about specifics. And these captains were proud men, more bird or fish with their knowledge of the winds and waves, so to say nothing against her insults must have been a hard thing. Still, I don’t know of any man who visited her cottage with the money and intent to buy that charm whose tongue or pride betrayed him, no matter how much his blood might have boiled. That’s small magic, as my grandmother would say, the small magic that keeps the world spinning.

When a man came to the cottage looking to own the winds, she would send him away until she was done. Once, a captain—an outsider, otherwise he wouldn’t even have bothered to ask—wanted to stay, to witness her magic.

“I work better alone,” she said, and the captain’s gaze slid to me, her six?year?old granddaughter, watching narrow?eyed from the corner. But if he thought anything, he didn’t say it aloud.

I didn’t want him there, either. My grandmother’s cottage was a world that belonged only to us, to her and me and maybe my mother, too, if she ever wanted it back. The Roe women made the magic that kept Prince Island running and had for generations, and that captain should be grateful instead of plain nosy. I scowled at him until he left.

My grandmother crossed to the back of her small cottage and reached inside a heavy black trunk tucked at the end of the bed. The trunk, as far as I knew, was as old as the witches themselves, a big, bulky thing that the first Roe brought with her when she came to Prince Island. It had been passed down since then, from mother to daughter, and it was where the Roe women kept their materials. The trunk should have gone to my mother years ago, but instead my grandmother kept it in the cottage, and although I had slept with this thing at my feet for my entire life, I’d never looked inside. I’d never been invited.

I could hear my grandmother’s long fingers gently pushing aside things that rustled and clinked until she pulled out a white cord as thick as my pinkie and as long as my arm.

“Here, Avery,” she said, sitting down in her chair, and I ran to her and climbed into her lap. She wrapped her arms around me, the fabric of her sleeves warm with the smell of woodsmoke and herbs. She held the white cord loosely between her hands and I laughed and reached for it like it was a toy.

“Not the cord, dear,” she said, lifting it from me. I felt her lips press against my hair, her breath warm against my scalp. “Lay your hands on mine.”

My chubby fingers twitched in my lap, and I lifted them up, where they hovered over my grandmother’s hands. Her skin was almost sheer, the network of pale blue veins standing out like tree branches. I walked my fingertips up the backs of her hands from her wrists to her knuckles, pushing hard so that I left a trail of pale dots on her skin.

“Focus now.” Her words tickled my cheek, and I slid my hands around hers.

The cord snapped tight between her fingers, every fiber fine and shimmering as though it were made out of spider silk. For all I knew, it was.

Faintly, my grandmother’s lips moved, lifting my hair, but I only heard the rush of hot air, and I held my breath, my eyes wide.

Outside, the wind arched around the cottage, a low, deep moan that shook the windows. Something clattered against the door, so loud and sudden that I jerked, but my grandmother gently pressed her cheek against my head.

“Focus,” she said again, her voice more air than noise. “Keep your eyes on the rope.”

The rope…It vibrated, shivered, and even though my grandmother’s sun?browned, lined hands remained steady I could feel the fine shudders through her bones. The wind picked up, a howl of such high pitch that it sounded almost like pain, but I didn’t dare pull my eyes away from the white cord, moving like the strummed string of a guitar.

“Granma?” I whispered, my heartbeat rising in little pricks. My palms began to sweat, my fingertips to shake and tremble, and I could feel something, something pulling at me, a force reaching through my fingers, through my skin, my bones, traveling deep inside of me, yanking, grabbing, clawing like a cat tearing apart a ball of string.

Tears rose to my eyes and I wanted to shrink away, but I couldn’t. My bones had turned to stone, while my grandmother said nothing, while outside the wind blew even more fiercely, rattling the glass of the windows, struggling to get in, to get at us, at me.

The air escaped from my lungs, and when I tried to breathe in again, I found that there was no breath, no wind, no air, as though an invisible hand reached down to pinch my nose and mouth shut and I was drowning, suffocating.

“Granma!” I wheezed, jerking, the rope buzzing between her fingers, the wind slamming fists against windows, howling at the door like an animal, maddened and maddening.

Every window burst open and I squeezed my eyes tight as the wind clawed at me, scratching my cheeks and twisting my hair across my face. My grandmother’s hands came together quickly, expertly, and my hands moved puppet?like on top of hers, working and tying the string, pulling tight. I screamed, a wail as high and pure?toned as the wind itself, and it was as though something precious to me was suddenly wrenched away, torn into the wind and gone forever.

“Shh… Quiet, love, it’s over now.”

My grandmother’s hands pressed heavily on my shoulders, and I realized my own hands were free. I hiccoughed and held my breath, my eyes still shut, and in the silence I could hear that the wind had died down, the air now cool and still.

I opened my eyes, blinking wide. My hands pressed against my chest, the muscles of my body sore as though I’d just carried something heavy for a long time. But it was only the memory of pain; whatever feeling had pierced me was gone.

“I didn’t like that,” I said, looking back at my grandmother. “It hurt.”

For a moment, it seemed as though she hadn’t heard me. She breathed hard, her skin ashen, her eyelids fluttering, and I frowned. She often looked like this, after big spells.

“Granma?” I reached a hand to her face and she shuddered, snapping her chin up. She laughed, a papery sound, and pressed the palms of her hands against my chest. Under the weight of her touch I could feel my own bones, thin but strong.

“That’s all right, dear,” she said, whispering slowly into my ear, her voice quavering. “It should hurt. That’s just how it should be.”

The cord still hung limp from one of her hands, and I reached for it. This time my grandmother gave no protest, letting me run it through my fingers and feel the three tight knots now twisted down its length.

“What did you do?” I asked, and I traced my fingers across each knot. If I pressed hard, I felt something deep within: a rumble, a barely?there thrum.

“What we did,” my grandmother said, taking the string lightly from me. “Each knot means the winds. Untie the first for a light breeze. The second will bring a fair trade wind. The third—that’s the strongest. The third untied means a hurricane, greater and more terrible than anything you can imagine.”

“Why would someone want to call a hurricane?” I asked, tilting my head at her. She lifted her eyebrows.

“I don’t ask, dear,” she said. “Remember that. It’s not our place to ask. Folks have their reasons.”

“Will I be able to do that on my own now?” I asked, and my grandmother shook her head.

“Not for a long while yet,” she said. “Someday, when you’re older, I’ll explain how the magic will come. But until then, you can help me.” She smoothed my dark hair with her hand, and I felt a warm glow in my stomach to be a big girl, old enough finally for my grandmother to include me in her work.

She eased me gently to my feet and stood up before walking slowly across the cottage to the black chest. She limped, moving as though her bones had grown stiff in the few minutes it took to work the spell, and when she reached the chest she put a hand on the wall to steady herself and breathed hard.

I watched her carefully, just in case she fell or collapsed. Sometimes it happened after big spells like these; sometimes she would rise to her feet only to fall again, crying and clutching her body, and I’d know to get a pillow to put under her head and push away the table and chairs to give her some space and shove my fingers into my ears to drown out her keening (only I didn’t tell her about that last bit). But she looked well now, and I thought it was probably because I had helped her, this time.

She lifted the lid of the chest and was about to drop the rope inside when she turned to me and paused.

“Come look,” she said, smiling, and my stomach swooped.

I walked slowly, my breath held tight within my lungs. My grandmother reached out an arm to me, scooping me close against her legs, wrapping me tightly as my eyes widened.

String, feathers, stones, simple objects, but to me they were jewels, shimmering with the memory of my grandmother’s magic. Beneath those little worked charms I could see neat stacks of papers, notes written in strange hands, diagrams and drawings I didn’t understand but that called to me, called to me as surely as if they already were mine.

I stared into the chest at my feet, the box that kept the history of the Roe women and their short, wild lives. It seemed too small. How could they shape my island, my world, so much and yet leave so little behind? But they also didn’t live long, the Roe women, lasting until their forties, just until their daughters were grown and capable of taking over for them—although my grandmother would soon prove to be the exception.

“That box holds generations of Roe history,” my grandmother whispered. “Everything we’ve learned or created. It’s been passed down from mother to daughter since the first Roe. My grandmother gave it to my mother, my mother gave it to me, and someday I will give it to you.” I looked up at her in surprise, and she leaned forward to press her lips against my hair. “You’re a part of them. A part of us.”

Us. She meant the Roe women, yes, but also the witches, the witch of Prince Island, for there was always only one working at a time. (My mother, for example, had all the abilities but it was my grandmother who was the witch.)

“It will be up to you, Avery,” my grandmother said, pulling me from my thoughts. “Do you understand?”

Yes. I knew just what she meant. It would be me, me and not my mother, who would take over for her and become the very next Roe witch.

I nodded, and my grandmother swept me up in her woodsmoke arms and held me close, and I thought about my mother, who had abandoned magic and me only a year after my birth, who had given up her place as the Roe witch and forced my grandmother to work long past her prime, making her weak and tired and worrying the islanders.

I was supposed to set it right, to become the witch and bring Prince Island back to the glory days, but before I could, before even my grandmother taught me how to unlock the magic that would have made me more than just her apprentice, my mother came back for me. Days after my twelfth birthday, she dragged me kicking and crying from the cottage on the rocks to New Bishop, the big town at the northern end of the island, and in no uncertain terms absolutely forbade me to become the witch.

Ever since then I knew it would only be a matter of time before I returned to the cottage, before I escaped. And when the days rolled into weeks, months, years, I didn’t worry, I didn’t panic. I did not care when my mother announced her engagement and then marriage to one of the island’s wealthiest men and moved us to his home. (What was one prison in exchange for another?) And when she began dressing me in silks and satins, parading me around like a prize pony at church picnics and social teas, lacing her conversation with words that felt like mines—gentleness, obedience, virtue, social grace—I hardly even paid attention. Let her do what she wanted. Let her fantasize about the kind of woman she wanted to make me become. I did not care.

Because I was supposed to be the Roe witch, it was my destiny and duty, and how could anyone, even my mother, stop that?

Well.

I tried.

I hope the people of my island know that, at least.

I hope when they tell this story, the story of how they lost their witches and their luck and their fortunes, they don’t judge me too harshly. I hope, also, that they remember none of it would have happened had my mother not turned her back on magic. Or had my mother left me alone in my grandmother’s cottage. Or had my mother, drunk on the cult of domesticity and stuffed to the brim with 1860s morality, not been so determined to see me a proper lady. Or had she realized that when it came to magic, I would not make her mistakes.

So if the people of my island blame anyone, better her than me.

Two

I was sixteen, still my mother’s prisoner,< the night I became the whale.

I am swimming and it is just sunrise, the sky so gray as to be almost invisible. I rise to the surface to breathe and that’s when I see the dark shadow of a boat, gliding gently toward me in the water. Men ride in the boat, their faces grim and greedy and silent, and as I turn to watch them I feel a bite in my side, a piercing pain.

The word harpoon forms in my frantic mind when I see another man lift a long, heavy metal spear to his shoulder to strike again, but I dive, dropping down through layers of water. The ocean turns cold, dark, pressing around me, but the deeper I go the more the iron inside of me twists and pulls and I know that I’m tethered to the boat, that even now the men pull the rope tighter and drag me back to the surface.

It does no good to swim, I know, but maddened with fear and pain, I press into the waves and the heavy boat tows behind me, casting up crests of waves in its wake. I swim and swim until the energy leaches from my burning muscles, energy that would have done better to be saved to fight, and now I can only pant into the water.

I lurch toward the boat, intending to attack, but they reach me first, a lance deep into my side. The rope connecting us tightens, pulls me ever closer, and the rising sun flashes against their bright knives. They aim not for my brain or heart but my lungs, and when the first knife hits, I gasp, breathing in blood and water and cold, cold air. Another knife hits and another, ribboning the pink tissue inside my body, and it’s like trying to suck oxygen through a wet sack. My panic makes me lurch for air again and again, but when I breathe now, blood and water spray into the air, a column of red that clouds around me, and I can taste them mix, salty water and salty blood, and just as my eyes roll back into my head, I see the bright curve of a hook, a hook the size of a man’s head, and I urge every last bit of strength I have into my scream.

It was then that I woke up, panting for air, my arms and neck glazed in sweat. I lay in the darkness, confused and blinking as the details of my bedroom solidified. Still heaving for breath, I sat up in bed, pressing my fingertips against my closed eyes until bright points of light shattered across my vision. My heart refused to slow, and I jumped from the bed and threw open the window, gulping in cold air.

I leaned my cheek against the edge of the window, the breeze cooling the damp hair stuck to my forehead. The world outside was drawn in grays and silvers, silent but for the soft nighttime sounds of birds, the rush of the black ocean only a two?minute walk from my bedroom. My chest ached, and I lifted a hand to press my fingertips against the cage of bones around my heart and imagined again the sailors’ knives, the harpoons.…

A nightmare. It was just a nightmare. A normal sixteenyear?old girl would laugh, shaking her head at her own foolish imagination before tucking herself back into bed. But I was not a normal girl, and this was not just a nightmare.

Every Roe woman receives a special ability, aside from water magic—a gift that appears in childhood and separates her from all the Roes before her. My grandmother could read high emotions, soothing and appeasing even the strongest passions. My mother—in a twist of irony that proved magic, at least, had a healthy sense of humor—had power over love, affection, and in her youth she would sell charms that promised love for the day, the year, the lifetime.

I could interpret dreams. I could see what they meant for the future, for the dreamer, and I knew what this dream meant for me.

For the first time in my life I thought I might not become the witch. I might not ever have the chance. Because I could read dreams and I knew what it meant to dream I was a whale, to dream of men trapping me, hunting me, piercing me with harpoons and leaving me to drown in my own blood.

I will be killed. I will be murdered. I’ve never been wrong before.

Three

Panic reared up through me, hot and blazing and blurry, and that was it. I had to escape to my grandmother’s cottage, and I had to go now.

I spun and threw open the door of my looming black wardrobe before shoving aside the woolen winter clothing folded in the back. There was a false bottom to this wardrobe, and if I hooked my fingernail just right into the far left corner, I could lift it up, exposing a space about the size of a man’s shoe. My fingers shook as I reached in, feeling in the darkness smooth stones, a handkerchief knotted around sand, a single delicate and empty bird egg: my version of my grandmother’s black chest but without the magic.

I felt around in the hole until I found a short length of twisted, rusty wire, the kind usually wrapped around a fence post. Sailors say a bit of fence wire could protect a man against a curse, and so I carefully wrapped it around my wrist, staining my fingers with powdery orange?pink rust.

This will work, I told myself, although I knew I had not made a spell and remained just a girl with some wire puckering the skin of her wrist. Still, I rose to my feet, my mind already racing through my escape: down to the kitchens, out the back garden, loop around town, then down to the beach and straight south to the cottage and safety.

I didn’t need a map, not when I knew almost from birth every inch of my island, floating forty miles east of Massachusetts’s shore. Prince Island from above looked like a comma with a stretched?out tail, a pause before the open ocean, and I pictured myself standing at the northeastern tip of that comma, where my mother’s house lay, and pointing my toes south, along the curving shoreline path all the way down, down, down to the very tip of the comma’s tail, to the crumbling rocks where my grandmother’s cottage sat. It would be a long walk, more than seven miles into the wind, but as soon as I left the town behind, it would be a nice walk, too, with nothing to my right but bowing fields of sea grass and nothing to my left but ocean. And then the sandy shoreline path would go brown and bare, sand turning to gravel turning to rock, and the land to my right would grow skinny and broken, and by the time the sun would rise, I would see the cottage before me, rosy with the dawn. The sky would be clear, colorless, mist blending together the air and the ocean, the waves whispering against the rocks. My grandmother would be inside, asleep, tired, maybe, from a long night of customers, and I told myself, I will walk through the door, wake her, and say, “I am home.”

My breathing slowed as I held the moment in my mind, and then I turned and reached for the cloak hanging on the wardrobe door.

This will be the night I escape. The thought repeated in my mind like a refrain, over and over, and I believed it so hard that I whispered it aloud: “This will be the night I escape!”

I took a step, one step with the cloak still bunched in my fist, and my knees gave underneath me.

“No!” I whispered, catching myself just in time. I clutched the wire around my wrist and urged it to heat with magic, to protect me. Another step and this time I fell to the ground, the sharp points of my elbows and knees striking the carpet so that I gasped with pain. Bright stars peppered my vision, exploding into color and then into blackness, raining down over me, smothering me with sleep, but even as I could feel my arms and legs go tingly numb, hot anger sprang through my veins.

Stupid! Why did I possibly think I could escape that night? For four years, any moment I attempted to run back to the cottage, the invisible rope around my waist gave a tug, tethering me back to my mother’s world. Cursed, I was cursed, and my mother said she’d given up magic for good, said it was a terrible thing, but she wasn’t above using it to keep me at her side, and she’s a hypocrite, a liar, a fraud and phony, and I hate her I hate her I hate her!

I stretched out on the carpet, eyes glazed over, my heart whirring with frustration and fear, and as my mother’s curse slowly, firmly, pushed my eyelids closed, my body went still. But on the inside I was screaming.

I woke stiff and light?headed, my bones and joints aching. The wire still dug into my right wrist, and my hand tingled. It had been months since I last woke up on the floor like this, caught in an attempted escape, and my cheeks burned as I pushed myself to my feet and slowly, gently stretched.

I massaged my aching muscles and unwound the wire, blinking and fuzzy?headed, when it all rushed back to me: the dream, the knives, my shredded lungs full of blood instead of air, and what it all meant for my future. My knees trembled and I had to clutch the wardrobe for balance.

I am going to be murdered.

It wasn’t any easier to face in the daytime.

Wincing, I leaned against the wardrobe, unused to the swooping, dizzying feeling of glimpsing my own future. I’d seen death in dreams before, of course: I discovered I could tell futures six years ago, about the same time more and more of our whale men signed up to fight in the War Between the States. My grandmother, ever the entrepreneur, set up a side business in future?telling that kept us both afloat during the war years (my grandmother had charms against whales, not bullets).

They made me famous, those dreams, and soon would?be soldiers began to visit the cottage not for the witch but for her little black?haired granddaughter. “Doesn’t come up to your elbow,” men would say, “but can tell you if you’re gonna live or die.”

I always suspected it was the dreams that attracted my mother’s attention, because when she came to the cottage and pulled me away, she hissed at my grandmother, “You’ve turned her into a death?teller! My child!”

My grandmother said something in response, that magic was my birthright, that I belonged here, that I was doing what I was meant to do, and my mother’s hands squeezed my arms so tight that they tingled.

“She’s meant for more than this.”

My mother forbade dream?telling, of course, but what she didn’t know was that I still interpreted dreams, down at the docks for pocket money, even though her new husband had enough money to fill my pockets for decades. It was the only way I knew to relieve the tension that I constantly carried inside, the magic that coiled inside of me, begging to be put to use. Boys and men would sidle up to me, a dollar a dream, and I’d tell their futures.

Often the dreams meant silly, unremarkable things—a missed kerchief, a spoiled meal, a bad sunburn. Every now and then, though, I’d see something terrible. I’d see the boy standing before me blistered with fever. I’d see boats smashed into splinters, men slipping into black water. I’d see disease, danger, death.

When that happened, I held their money out and told them: “It isn’t good. Do you still want to know?”

No doubt my business?minded grandmother wouldn’t understand, but I think it’s only fair. A bad death is a terrible thing but so also is to live your life under a shadow, asking with every moment or decision, is this it? Is this what will lead to my ruin?

Sometimes they still wanted to know, would rather have the knowledge, and sometimes they took their money back and said they’d rather just let what’s fated happen. Sometimes afterward, after I told them all I knew of their terrible futures, they laughed and said it’s all foolishness and they didn’t believe me, which I didn’t mind—after all, it wasn’t my life.

Other times the sailors with the bad futures would ask me a question: “What can I do to stop it?” They’d ask me and I’d shrug. Can’t do anything. It’s the future. Can’t change it. Then I’d leave, and quickly, before they demanded their money back.

But for the most part, telling dreams was fun for me, a lark, a way to try on the mantle of the Roe witch and prove to the people of the island that I was more than just my name and bloodlines. I liked doing it—or used to, I thought, and my fingers trembled as I buttoned up my dress.

“Calm down,” I whispered, and the knot in my stomach twisted. “You’ll gain nothing by panicking. The dream won’t come true. It can’t come true. You’re not supposed to die, you’re supposed to become—”

My words broke off as the answer came to me.

You cannot kill a Roe witch.

It’s an old island saying, dating back to the very first Roe, Madelyn. More than a century ago, when Madelyn came to the island, a whipped?up mob plotted to throw her into the sea, but the wave that reared up from the rocks swept away not the witch but the would?be killers. Since then, grieving women and angry sailors, come to seek revenge on the witch, find their knives turned and their passions cooled. It’s been proven true too many times to be mere superstition. You can’t kill a Roe witch.

The thought filled me with relief. True, I was not the witch, not yet, and so not safe, but there was a solution. All I needed was to unlock the secrets of my magic and take over for my grandmother.

Laughter bubbled up through me, high?pitched and nervous, because I’d been trying to accomplish this for four years now and was no closer than the day my mother took me away.

What else could I do, then? I didn’t know how to access my magic, how to transform into a real witch, but my mother knew. My grandmother knew. My mother, of course, would never tell me, but I was certain my grandmother would. If I could only send her a message…

I rubbed my temples, a headache growing at the very thought. My mother had forbidden messages between my grandmother and me. For four years now we heeded her because on the day she took me away, my mother had shouted the one thing none of us could have possibly expected: that if my grandmother ever tried to come for me, my mother would take me off the island.

What a thing to say, for what Roe, even my magic?hating mother, could have chosen to actually leave the island? Leave her home? Leave the only world she knew? It was as though she’d suddenly held a knife up to my neck. So strange, so reckless and violent, and while I doubted anyone—not my grandmother, maybe not even my mother—would have actually thought her any more capable of taking me off the island than slitting my throat, one does not test a madwoman with a knife.

Goose bumps prickled across my skin as I imagined her on that day, wild?eyed and wicked. Would she make good on her threat if she found out about a message? I’d been too scared to test her these past four years, and I knew a message would be dangerous, and it would be foolish.

But I was desperate.

Decided, I moved quickly out of my room, through the hall and down the stairs and out the front door, taking care to muffle my footsteps, although it was so early that I doubted anyone was awake—not my mother, not her husband, not his two rotten little children.

Your new family, my mother called them, and they were perhaps the worst of the many indecencies she’d forced me to suffer. I didn’t believe my mother at first, two years ago when she came back to the oily, ramshackle little apartment where she had taken me and told me that she was going to marry William Sever, a pastor (pastor! Can you imagine my grandmother’s heartbreak when she heard the news?) and wealthy widower with two small children: six?year?old Hazel and the terrible Walt, a boy whose primary interests seemed to be smashing insects and spying on his new stepmother in the bath.

Outside on the front lawn, I paused a moment to check that there weren’t any little faces watching me from the windows of the pastor’s big, glorious house, pinkish?white and perfect in the morning light. The house fit in with my mother’s obsession with money and status, although when she first took me away, she seemed content enough with her modest life as a washerwoman. She claimed, often, over and over, that she married the pastor for me, to get me out of the cramped apartment, away from the refineries that kept me coughing, and into good clothes and a warm bed. But it was obvious that she enjoyed being the lady of a grand house, living in the nicest neighborhood on the island (a place the locals called, with airs most decidedly on, “up lighthouse”). And she was forever telling me how much better, how much safer our lives were now.

Safe, I thought, turning my back on the house, and the word sent a shiver down my back. Safety was important to her.

You can’t kill a Roe witch, but you can beat her within an inch of her life, and that is what happened to my mother. Once, she’d been a beauty, impossibly lovely, with a face that made her more famous than her love charms and that set her apart from the other island girls, short, round?cheeked, grayeyed, freckled, with wide mouths and noses that flattened out near the eyes and hair as wild and stiff and tangled as a mat of dried?out seaweed (this is what I look like, at least).

I don’t know the particulars of the story, for my grandmother, whenever I asked, just pinched her mouth into a long, straight line and said nothing, but from what I pieced together from rumors and whispers, my mother had been young, teens, maybe, or early twenties, when a man beat her senseless and split open her lovely face from right eyebrow to the left corner of her lips (a small point: that man was my father). He left her with a baby and a scar and a devastating hatred for magic, which, in the end, had not prevented a half?drunk brute from taking away the only thing that had made her truly special.

She put her faith in money instead of magic now, but money wouldn’t do a whit for me and my dreams, and I shoved open the beautiful wrought?iron front gate and stepped out onto Main Street. With the beach and water to my left and the homes of the island’s elite to my right, I walked south, watching for any spying eyes: nosy society ladies who would love nothing more than to march over to Pastor Sever’s home and tell my mother my doings (she had spies all over the island, and it was common knowledge that if a man saw the little Roe girl out of bed in the middle of the night, there’d be a fine reward for her return).

Gradually, the houses to my right grew smaller, humbler, and closer together, flapping sheets of laundry instead of manicured hedges decorating the front lawns. Unlike the richies in my mother’s new neighborhood, these people were already out of their homes and at their work, and they knew me and nodded at me as I passed.

“Good morning, Miss Avery,” one woman called, folding a sheet against her body. I waved back, recognizing her as the wife of a sailor still at sea. I had a delicate relationship with the people of my island. They loved and respected my grandmother and they feared and respected my mother, but I couldn’t help them, not yet, and they watched me warily.

The houses thinned out as I reached the first of New Bishop’s stores: dark and huddled dry goods, the mustywindowed milliner, the bright white apothecary where already a crowd of children stood outside, staring in at the jars and jars of dream?colored candies. My grandmother had once toyed with the idea of setting up her own little shop in New Bishop, to lure footsore sailors unwilling to trek out to her cottage. But of course, she hadn’t come near New Bishop for four years.

Main Street narrowed as I continued to walk south into town, the buildings rising ever higher above me to crowd out the view of the sky and the ocean. The path underneath my feet turned to brick, the road to my side cobblestone, and when I inhaled, the sharp smell of coffee filled my nostrils, raising the hairs on the back of my neck. Low?ceilinged restaurants and food stalls erupted with the sounds of working men getting their breakfasts: sugared honey buns, fried sausages, wire baskets of clams that steamed and shivered water in the cool morning. I’d missed my own breakfast and couldn’t help but pause and stare, my mouth watering, as a red?faced baker’s wife laughed with a dock boy and wrapped up in a bit of newspaper a hot cake crumbling with heavy?scented cinnamon, her fingers leaving greasy smudges in the ink.

Beyond the breakfast market, the fruit and vegetable stalls crowded the already busy sidewalks with sweet rotting smells. Even this early, the women of Prince Island scoured the wares, shallow baskets swinging over their muscled arms, while a group of men sat huddled outside the green door of the tobacco store, the de facto meeting place for the island’s whaling agents. Most of these men didn’t share the island look of gray eyes and dark hair, and I could tell they were outsiders (the polite term is “off?islander,” but behind their backs we call them “seagulls”). Still, they knew as much about the island’s businesses as anyone, as they were responsible for manning whalers, negotiating sailors’ contracts, running the business of whaling for the ship owners. Ringed in blue?gray smoke, they talked about the whaler schedules in loud voices that quieted as I drew nearer.

“Just one goin’ out this week,” a fellow with a thatch of red hair said to the group, and as I passed, his eyes narrowed and he called out softly, “Give my regards to your grandmother, Avery Roe.”

I nodded at the men, their wolfish stares following me, and turned east onto Water Street, which led to the ocean and the docks, but had I continued walking south on Main Street, I would have run smack into the factory district, made up of boxy, sky?high buildings that belched black smoke morning to night—or used to, back when I was a child, when my grandmother was younger, when there were more whales in the world. The noise of the market and the stores faded behind me as I walked down Water Street through the shipyard, the blocks bordering the great wharf that stretched down New Bishop’s shore. Men too old or too disinclined to sail often set up shop back on Prince Island to build and repair ships, and in the glory days the widened streets of the shipyards teemed with men and with the bits and pieces that made up the great whalers. Most shops would leave their doors open during the day, the better to bring in business, and a man could look left to right and see riggers busy twisting hemp into rope, coopers making careful planes down pure?white oak boards, blacksmiths grimacing as they lifted their hammers over sizzling red iron.

Today, though, mist rose over the empty shipyard streets. Half the stores were closed and had been for months, while in the other half, artisans meant for turning wood and metal into whalers instead swept their floors, cleaned their hearths, or sat on stools, hands clasped, talking in soft, absent voices.

A few watched silently as I hurried down the street, and Martin Child, a canvas maker, leaned out the door of his shop, lifted his chin, and called out, “Hey there, Avery Roe.”

I turned to look at him and tendrils of fear snaked through me to see his hard expression, something almost like an accusation sitting in his familiar island features. He wasn’t a sailor—none of the men in the shipyards were anymore—but they were islanders and still lived and died by the business of the whalers. A man on Prince Island was a whale man or he was a shipwright or he worked in the bank, financing excursions, or he worked for the ship owners as a whaling agent. Foreign sailors often visited and bought my family’s charms, but the people of the island were the ones who truly relied on us. They were waiting for me, my islanders, waiting for me to take my grandmother’s place and bring them back to glory. But I could feel their patience begin to wane as business trickled, could feel the lingering eyes of the shipwrights as I passed through the yard. I thought then of my dream, my nightmare, the cold, chilly faces of the sailors, and I shivered and picked up my pace.

Beyond the shipyard, Water Street ended at the docks, spread out a mile and a half down New Bishop’s shore like brown and broken teeth. The exact middle of the docks, Main Dock, still catered exclusively to the big, square?rigged whalers, but the farther from Main Dock in either direction, the smaller the boats got, from whaleboats to fishing boats to sleek, rich sailboats, all the way down to rowboats, dinghies, and even a few flat?bottomed skiffs.

There was a time when so many ships crowded the docks, it was as though Prince Island’s stubby, wind?stunted trees suddenly grew into a forest of masts and ropes and curled?up sails. Skyscrapers, the islanders call them, the straight black masts stretching three, four stories into the air to scrape the sky. But that was before whalers began hunting up north, before their ships got trapped in Arctic ice, before whales learned better to hide from hunters. That was before the War Between the States, when whaling grew so dismal that instead of sending their ships out on hunts, owners sold them south, to be filled with stones and sunk to the bottom of rivers, channels, harbors, all the better to keep the Confederacy closed off from the sea. All those lovely old ships, broken up and flooded, worth more as detritus and debris, and the owners shrugging away complaints, saying “What else am I to do? What else can I risk with the whales gone and the ice biting and the Roe witch unable to offer her protection?”

I headed straight for Main Dock, which in spite of everything still swarmed with men and boys, running, dragging ropes, or rolling barrels, their movements as chaotically in sync as a great school of fish. So much blood and waxy oil had seeped into the wood of the docks over the years that they were permanently stained, marbled dark rust and greasy gray. You had to shout to be heard down on the docks, shout over the noises of creaking ships, snapping sails, the constant hammerfalls and saws of the repairmen. And it always stank: of salt and brine and sweat, of rotting whale and sweet oil. In short, the docks were an affront to every kind of sense and, aside from the cottage on the rocks, my favorite place on the island.

I descended the rickety stairs to the docks without slowing, crossing the invisible line that separated the island’s women and children from the world of the whalers. These men knew me, knew my grandmother, and they lifted their eyes from their work to greet me. They weren’t just islanders, gray?eyed and dark?haired, but foreigners, too, of every continent and coloring, their g’mornings accented in French, Spanish, Portuguese, the lilting of the Southern states, the trill of the Pacific Islands.

“Hey there, Miss Avery,” a red?faced man said, but when I nodded and meant to keep walking, he put out a hand. “Think you can make me a spell?” He held up a slim, six?inch?long metal spike attached around his wrist by a cord: his marlinspike. Good sailors had to know how to splice together ropes or quickly undo knots, and my grandmother had a tincture of whale oil and saltwater mud that made the marlinspike slide through even the tightest knots and kept its rope splices tight. But even if I hadn’t been distracted by my nightmare, I couldn’t make him the spell.

“Go see my grandmother,” I said, and he scowled.

“I did. Made the walk last night, there and back, but she refused.” He ran a thumb down the point of his marlinspike. A shiver worked through me and I frowned, because this was the second time this week I’d heard that my grandmother turned a sailor away. “What’s she getting on about, sending me off? I had good money and my feet felt none the better for the walk.”

“I’m sorry,” I said. “Perhaps she was tired.”

“She was tired, eh, but what’s your excuse, then? Since when do the Roes think they can refuse us?”

“She would do it if she could,” I said, and I frowned as a headache began to grow behind my eyes.

“And what about you? Can you do it, or d’you think your name alone gives you the right to act high and mighty down on the docks? You say you’re a Roe, but all I see’s a fancy little girl who likes to play at magic. This is my life! You’ll play with that, will you?”

“I have to go,” I said, and I pushed past him and rushed down the dock before he could say anything else.

“You’re her? You’re Avery Roe?”

Surprised, I spun quickly to see another man—no, a boy, only a few years older than me—standing behind me, his head cocked to one side. He had the coloring and look of one of the South Pacific islanders, whale hunters prized as harpooners and oarsmen, but he spoke nothing like those men I’d met in the past. Living on Prince Island had given me an ear for accents, and this boy’s words rang with a mix of cultures: a bit of British, some French, even the casual slang of New England sailors.

“I am,” I said, my heart still buzzing from the sailor and his marlinspike, “but there’s somewhere else I have to be. Good day.”

I made to move, but he held out a hand, smiling, his teeth white against his cinnamon?colored skin, and reached into his pocket, where I heard the jangle of coins. “I would be willing to pay you for your time,” he said, and when he drew out his hand it shone bright with silver dollars. “I have a dream for you.”

My eyes traveled from his outstretched hand up to his arm, where an intricate checkerboard pattern crisscrossed his skin, beginning below his elbow and disappearing under the roll of his sleeve.

“I can’t,” I said, looking over his shoulder into the crowd at the end of the docks. I needed to find someone. I needed to send a message to my grandmother. I needed to become a witch and stop my own dream before I worried about someone else’s.

I realized the boy had said something.

“Excuse me?” I said, and although he smiled at me, patient, there was a hunger in his eyes.

“I said that I’ve heard stories about you. I came to the island just to see you.” The light caught the coins in his palm, and when I glanced down I noticed that the long fingers of his outstretched hand trembled. “Will you tell my dream? I would like to know what it means.”

He came to the island just for me. That’s the way it used to be, when I was ten years old in my grandmother’s cottage, holding court before a group of awestruck men as I described their futures in detail. I liked that feeling, being needed like that, but something pulled at me with this boy’s words, an instinctual tug just below my rib cage, a warning.

I blinked, dazed, and he stared back at me, the smile on his face stretching with a look I’d seen before—desire, pure and all?consuming. This wasn’t idle fortune?telling, and again the warning flashed.

“I can’t, I—” The words froze on my lips as a sudden, sweeping wave of need crashed over me. The magic inside of me whipped up like a maddened dog, desperate to be put to use, to tell this boy’s dream. I needed to tell dreams. It eased that terrible, constant pressure in my chest, if only for a little while, and even though I charged money for it (don’t give them anything for free, my grandmother told me), it was as much a service for myself as my customers. And now, the magic inside of me screeched, a hungry baby howling for food, grating and constant and shrieking through my head do it do it do it DO IT, and I stuttered and stopped myself, overwhelmed. “No, I mean, all right. Tell me your dream. Quickly.”

He pushed his handful of coins higher, eager despite his passive face, but I only plucked one from his palm. “I charge a dollar,” I said, my voice tense, and he nodded and slipped the rest back into his pocket.

“You have to tell the truth,” I continued, and I heard a soft laugh behind me. When I turned, I noticed that a small knot of young boys had paused their work to watch us, and my stomach twisted. The boys laughed because, lately, it had become sport to make up dreams for me to tell: wild, naughty, stupid dreams that made my head ache and my temper flare. “All in good fun!” they’d tease, because I wasn’t my mother or my grandmother; I wasn’t a proper witch and they didn’t care about me. They didn’t respect me.

The tattooed boy, to his credit, ignored them, and when I looked back at him, he began.

“I am alone,” he said, his voice rumbling up through his lungs, through his throat. “It is night, and I am in the middle of the ocean. I float in a canoe, and I am flat on my back, staring up at the sky.”

I felt it then: the sloping, slipping curve of his words, reaching out for me with spider?silk threads. He wasn’t lying, not like the dock boys did; this dream was true, but I couldn’t shake the feeling that something was wrong, the meaning of his dream slipping in and out of focus.

“The sky is full of stars,” he continued, staring into my eyes. “I watch them grow bigger and brighter. Then, one by one, they wink out and disappear until the sky is black.” He paused, and I bit the inside of my mouth, uncertain.

“I sit up and shout,” he said, and his voice grew soft, but the kind of softness that means excitement. “But there is no answer. When I look around, the canoe is gone and I am in darkness.” He lifted his hands into the air. “Then I wake up.”

Those spider?silk threads wound around me, pulling out the meaning of the dream, and as it fell into place, my hands jerked into fists. I took a deep breath and pressed my fingertips against my temple, massaging away my headache. Not this, not after my own terrible dream.

Another breath, and I held out his money.

“It’s not good,” I said, because it wasn’t. It wasn’t anything I’d be happy to tell a person, and I felt a stab of pity for this strange boy. “If you don’t want to hear, you can have your money back.”

For a moment he watched me, his brown eyes deep wells, and I thought perhaps he would take back his money. I thought perhaps that no matter what he said, I’d give him the money and keep my mouth shut. But then he shook his head.

“I have to know what it means.”

As he spoke, the full meaning of his dream slammed into place, and I understood suddenly why this felt so strange, why I shouldn’t trust this boy. All the pity inside of me vanished as my cheeks grew hot with a mixture of anger and embarrassment.

“I told you not to lie,” I said, and at my words, the boys watching us let out a swell of laughter. I turned on them, eyes narrowed. “Did you put him up to it? Told him it’s great fun to lie to the witch?”

They only howled more loudly, slapping shoulders and knees and stomachs, and I pushed past them, shaking with so much rage that my vision blurred.

“Wait!” the boy said, his footsteps close behind me. “I didn’t lie!” He ran to my side and threw an arm out to stop me. “That dream was the truth!”

“But you already know what it means, don’t you?” I said, spitting out the words, because that was the strange thing I felt: certainty. Some other witch somewhere else in the world already told him this dream and so his hiring me was all a farce, just another joke like the dock boys, another chip at my family’s moldering reputation. “Why ask me something you already knew?”

“You could tell?” He stared at me, stunned, and I squared my shoulders and moved to sidestep him. “Please,” he said, moving to block my steps. “I’d heard rumors of your magic but I needed to know for certain if you could really do this. I wanted to test you to see—”

“Test me!”

“Good one, there!” a boy shouted. “Yes, give her a test! She says she’s a witch but I think it’s all stories!”

They exploded into laughter as my whole body shook red hot, and I turned on the boy, fuming because he didn’t believe in me, because he thought he could expose me as, as a cheat or a charlatan or a trickster! It made me sick.

I hated this boy. I hated him worse than any of the pranking dock boys, and I wished I were a man so I could punch him and it would hurt or a witch so I could curse him.

I was not a man. And I was not a real witch. But I could still hurt him.

“You want to hear your dream?” I asked, raising an eyebrow. “They’re dead.”

He flinched, and despite the flicker of pity I felt, my temper carried the words from my mouth.

“You had a mother and a father and three sisters but now they are all dead. All your cousins, your aunts and uncles, all your friends, every person you grew up with is dead, and they were murdered and their bodies thrown into the sea.”

He stared at me, his dark eyes glassy with tears, but I just lifted my chin and rode out the waves of anger sweeping through me.

“Don’t bother me with your dreams again,” I said, and this time when I pushed past him, the boy didn’t stop me.

Salt & Storm © Kendall Kulper, 2014